What I want to question are the implications of a commonly asserted periodization; namely, the idea of the postmodern, summed up by Lyotard’s maxim on incredulity toward metanarratives. It seems that this idea of the postmodern may blind us to certain political and cultural realities that merit attention. Lyotard’s theory, like any theory is something of a microscope, allowing for insight while narrowing our focus. It may be the case that Lyotard captured in his theory an important intensity, a specific singularity of the era in which he wrote. Granting this, we have lived through some decades and many events since that time, and a critical revisitation of the idea of the postmodern is in order. In this essay, I hope to show that the incredulity that Lyotard made famous was not specific to his era; in fact, it had been at work in history for decades before he encountered it. If we accept such a vision of the postmodern, we may be accepting both more and less than we expect; in an era like our own one that seems to be possessed with a neo-medieval level of fanaticism and millenarianism, we may be sacrificing more insight than we gain. I will being with a discussion of Lyotard and a discussion of metanarratives and eschatologies; following that I will contextualize Lyotard’s theorization of the postmodern with the Nietzschean and Heideggerian theorizations of nihilism, and finally with contemporary political and cultural events.

I. Background

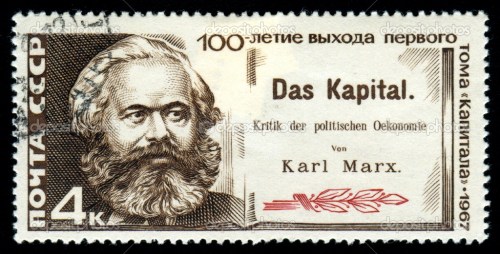

A metanarrative is a story that would give universal meaning to history. There have been many metanarratives, and two of the most common are Christianity and Marxism, though there are many others. The Christian and Marxist metanarratives can also be called eschatologies, this word comes from the Greek for “last” (eschatos) and “study of” (-ology), and an eschatology is a story that is concerned with the ultimate destiny and meaning of the world, and of life. Both of these ways of thinking see history as a plane of unhappiness and alienation. The Christian eschatology culminates with a transcendent agency annihilating history for the sake of a higher realm, while the Marxist narrative ends with people within history bringing it to a close by ending alienation and exploitation through political and economic action. So, we can see that both of these eschatologies include much discussion of history, but culminate in something other than history. As a sort of midpoint between these two, we have the meta-narrative of Enlightenment modernity; according to this narrative, history is the story of the bold fight of an enlightened elite struggling to protect accumulated scientific knowledge and principle of the application of Reason to public institutions from superstition and authority; protecting the idea that public life should be based on freedom and equal rights and the idea that through change and action we can make life better.

According to Lyotard, people are increasingly skeptical toward this type of story. Something seems to have changed in the relation between the people and certain metanarratives. It seems that the once liberatory narrative of Enlightenment and modernity has lost its street credibility in the wake of a number of developments in the world including the betrayal of the revolution by Stalin, the abandonment of the revolution of ’68, capitalist incorporation of trade unions and workers’ parties, and so on. It has become increasingly apparent that the metanarratives of opposition and liberation, in order to remain metanarratives, needed to be complicit with the very power structures they would liberate people from. It can also be thought of as the autocannibalism of Reason, which neglected to neglect itself in the work of demystification.

II. Lyotard, Nietzsche, Heidegger

How does Lyotard’s postmodern condition look when we bring it into relation with Nietzsche’s “Death of God”? In the wake of this death, any transcendent value system, any beyond, becomes unbelievable; this includes knowledge, truth, reason, good, evil, and the other members of the secular pantheon. The rug is pulled out from under all symbolic values, especially those that propped themselves up against religion. In order to explain modernity and the transition from modernity to whatever follows, we should refer to two quotes from Nietzsche, first his statement that “God is dead; but given the ways of men, there may still be caves for thousands of years in which his shadow will be shown.[1]”and second “The event itself is far too great, too distant, too remote from the multitude’s capacity for comprehension even for the tidings of it to be thought of as having arrived as yet.[2]”

Thus, we can understand ‘modernity’ as a bubble that opened up, wherein God had died or was dying, yet the residue of theology was left behind and adapted to ‘worldly ends.’ It seems that Lyotard is heralding the arrival of that death on a scale larger than was to be seen in Nietzsche’s day. However, this death is a process underway since long before the postmodern era; looking to Nietzsche, we see it underway in the late nineteenth century. Nietzsche’s thought on the matter of nihilism had a disciple of sorts in Martin Heidegger. Heidegger’s essay, “On the Question of Technology” is highly relevant for understanding the arrival of the death of God in contemporary society, and the technological nihilism that comes with it. First, we see the prevalence of one-dimensional technological rationality on an unprecedented scale. With this, we also face the increasing identification of being as a standing reserve, this includes knowing and thinking. Second, and inseparable from the first, we can see the revival of the Platonic doctrine of the noble lie by the neo-conservative movement; we can call this irony or cynicism, depending on our point of view, but it is a gesture of bold and daring nihilism. Between these two thinkers, we can see the ‘postmodern’ theorized under another name, namely nihilism, and it is my interpretation that Lyotard is recognizing a moment in the history of nihilism when he speaks of the postmodern. It seems that Lyotard attributed to the postmodern an unwarranted singularity as if some kind of rupture had occurred, when it is best viewed as a moment in the history of technihilism

Based on this context, there is much to be commended in Lyotard’s reading of the postmodern, but it seems that he was blind to the continuity involved. His summary definition of postmodernism can be assimilated to a preexisting explanation as put forward by Nietzsche and Heidegger. One can even be so bold as to claim that the era of technihilism began definitively with the industrial revolution. It is during this so-called revolution that God was displaced by economics, by economy or efficiency in the more precise formulation. At the time they occurred, one could easily have defined the enlightenment or romanticism as an increased credulity toward metanarratives, the metanarratives of Christianity and Reason specifically. However, the watershed event was the displacement of the meaning of the term primum mobile from God to the engine. Lyotard was somewhat correct because technology has become more powerful, technihilism more triumphant in recent history, but it was a quantitative change, not a qualitative one. We are still living in the age when nothing is true and everything is permitted. The age feared and touched only in nightmares by all previous civilizations. We are still tinkering with the same bourgeois values of science, efficiency in production and so on that inaugurated the bourgeois epoch. We are now feeling the implications of discoveries and changes made in the past, the present will only catch up to us in the future.

A proper theorization of postmodernism, if it is to be asserted that we live in such a time right now, would be content to accept the death of God and the rise of technological nihilism as background. It is a very good basis, a good context into which to place a theorization of the postmodern, as we have seen that postmodernity is a moment in the history of nihilism. What a good theory of the postmodern needs to do is to find the particularity of the postmodern as it stands over against the other moments in the history of technological nihilism. Lyotard’s formulation can only leave us hungry in that respect as it draws attention to the nihilism and the technologism without looking for the concrete instantiations the details of how that is playing out in the current day. If we place such a theory as I think it should be placed, different things, different features of the current time become salient to the investigator, become theoretically interesting. Lyotard, thoughtful though he is, may not prepare us for what we are dealing with today; his theorization does not provide us with tools for handling the change in the means of relating to metanarrativity which I feel characterizes the current era, the shift from modernist perspectives that deal in necessity to perspectives that embody a consciousness of radical contingency.

III. Strauss, Detournement, Populism

There are a few metanarratives that are flourishing right now. One of them, and the most farcical of all, is the neo-conservative oligarcho-imperialist populism metanarrative. As Thomas Frank once said, neoconservative propaganda in the United States is a recycled version of the socialist/populist rhetoric of the 1930’s shorn of its economic content [3]. This makes sense considering where the neoconservative movement comes from; many of the first members of this movement were disaffected liberals and socialists who turned to the right during the Nixon administration. Thus, a conservative politician will tell us how the little man needs to be protected from excessive taxation of big business. This sort of farcical adaptation is closer to the heart of the postmodern than public skepticism regarding metanarratives; the public is eager for the populist narrative, in the face of the absurdity of the narrative one is almost led to posit an overcredulity rather than an incredulity. This operates in conjunction with a second metanarrative; the metanarrative of market-driven globalization which one can say, without much hyperbole, is the apotheosis of technological reason. Another flourishing metanarrative is the war on terror/west vs. the rest metanarrative, the one that currently motivates the practice of many of the nations of Western Europe and the United States of America. Finally, we have the triumphalist “we beat the Russians” metanarrative; which has been discredited in part (‘the end of history’) but retains the power to overwhelm any contestation regarding the truth of justice, in a way similar to the war against the Persians worked to justify the Athenian empire during the Peloponnesian war.

If we want to understand what we are living, we need to revisit Lyotard’s formulation and contextualize it within contemporary political events. While we can say that Karl Marx was the most influential political philosopher for most of the twentieth century, we may have to concede that thus far in the twenty first it has been Leo Strauss, the contemporary of Heidegger, and the patron philosopher of the neo-conservative movement. The Rudolph Giulianis, neo-conservatives, the Nixonians, the Reganites, the Thatcherites, these are postmoderns, these and the broader movement they are a part of are emblems of the era in which we are living; an era that has more in common with a Christian Fundamentalist punk band than it does with The Velvet Underground. We are now living in the age of the conservative revolution, the bizarre and monstrous inversion of the traditional distribution of ideas. We must recognize that the conservative revolution and all that comes with it are as essentially postmodern as the drive to local struggles in progressive politics. It is the other face of postmodernism that Lyotard’s theorization may shift our attention away from.

In this era the political ground has shifted under our feet revealing a radical contingency, we come to see that there is no necessary connection between forms (artistic or social) and positions within the class struggle, that all of these correlations come about through contingent historical articulation. We are living in a time characterized by a bizarre detournement in which conservative cultural revolution has become a serious force in political life. An excellent example of this is Bob Roberts; a film written and directed in 1992 by the American actor Tim Robbins. In this film, Roberts, a conservative folk singer and businessman, runs for a seat in the senate, all the while recording albums that contort the music of Woodie Guthrie and Bob Dylan into the shape of the resurgent right. It is very much as Marx said in the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Naploeon, “ Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.[4] ”

As any person who knows a young republican/born again Christian/or jihadist can tell you, in this period there is no shortage of zealots of every kind; true believers swarm us from every direction, parties, religions, cults and so on have no shortage of followers. If we stick with a definition of the postmodern condition as skepticism, we render ourselves blind to the culture of farcical detournement, as well as the fact that our world is characterized by an almost medieval zealotry for metanarrative; it is best to view Lyotard’s pronouncement as an aspect of a moment in the development of nihilism, not as a new epoch in human history. If we must advance a definition of postmodernity our focus must be on radical contingency and reversal not on skepticism, it must be on appropriation not on contemplation.

[1] Friedrich Nietzsche. The Gay Science, Tr. Walter Kaufmann. New York: Vintage, 1974, pg. 167, #108.

[2] Ibid, pg. 279, #343.

[3] Something like this claim can be found in his What’s Wrong with Kansas? Though I paraphrase from memory.

[4] Karl Marx. The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon. http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1852/18th-brumaire/ch01.htm