Laclau Notes Session 4: Contingency in Theory

by Mark S. Lennon

1. Back to the Ancients

The most ferocious attack on Rhetorical Theory came from Plato. He claimed that rhetoric had no epistemological value at all. Rhetoric is concerned with the discursive movement of deliberation and not the question answer and two term choices which dialectic employs. In the Gorgias, Platon condemns rhetoric because it offers no coherent account of its own status as a form of knowledge, and because it is not possible to delineate a class of objects with which rhetoric is concerned. Rhetoric is nomadic; it has no specificity and no domicile. It is to be considered defective and incomplete by a Platonist because it offers a false ontology; it deals with the appearance of truth and good not the definition of the truth or the good. It offers no epistemological certainty or foundation. Above all, Plato judged rhetoric to be an amoral instrument of practical politics, unlike ontology and epistemology of course. A paradox emerges from this account: though rhetoric is tangible and deals with the tangible its arguments cannot stand up to critical scrutiny.

In the Phaedrus, Plato presents his dream of an acceptable rhetoric. This rhetoric should deal with figures and their effect on the soul. It should study kinds of arguments based on verisimilitude. At all times rhetoric should be a complement to philosophy, it should always remain secondary. As Plato says, “Unpack the riddle of rhetoric and it can go free.” This is quite similar to his treatment of poetry where the poet can provide a justification of poetry which allows poetry to go free although it is condemned. When Plato discusses rhetoric he usually gives us the figure of the sophist to direct our scorn at; however, we should not be fooled by this covert argument, we should not associate rhetoric with sophists because, as Aristotle will demonstrate, it in fact plays a large role in human affairs. Finally, since Plato’s death Lenin and other philosophers have destroyed the idea that ontology and epistemology are not political instruments. One could even say that Plato transfers(in the psychological sense) the politicity of these other areas of inquiry onto rhetoric, and that it must be the whipping boy for all the areas, which is why it takes such a beating in Platon.

Aristotle’s position on rhetoric was quite different from that of his master. Aristotle held that most of the things about which we make decisions offer us no chance of apodictic epistemic certainty. Hardly any of the decisions we make are determined by necessity, the answer that we will come to is contingent. There is a set of possibilities and there is no absolutely binding reason to choose any particular possibility. We use rhetoric is lieu of logical proof in these instances. Aristotle maintained that we use ‘phronesis’ or practical wisdom in these cases; this justifies his much greater openness to rhetoric. Aristotle’s contingency thesis demonstrates a new way of approaching rhetoric. This thesis displaces Platon’s reality/appearance duality into a distinction between necessity and contingency. Second, it claims that rhetoric is not epistemologically deficient, it refers to a different knowledge (phronesis) which is not scientific but social and political. It also shows that linguistic opportunism is not a valid argument against rhetoric because rhetoric uses language to deal with a confused social reality, it is a bricolage according to Burke. The opportunism is not rhetoric’s fault. Aristotle uses this hypothesis to remove the Platonic stigma from rhetoric. For Aristotle contingency is the mark of any kind of human action because people who act one way could have acted another way. A contingent truth is one which is not determined by the essence of the thing for which it is asserted. Arsitotelian contingency is opposed to necessity, it cannot be mastered by any chain of necessities, and it must be read with probability. We can speak of 2 types of necessity: absolute necessity which is known from intuition or self-evidence, and relative necessity which is deduced from reasons or demonstrated. We can also speak of 2 types of probability epistemic probability which refers to the degree of warranted belief based on evidence (Hacking) and aleatory probability which is related to the relative frequency of an event taking place. Contingency can also be understood in terms of the distinction between internal and external. The external is that which gives results but does not appear to be subject to any rule; the internal is related to human nature and social life.

If we admit that full rational demonstration is useless in many human situations what can we do? We can move from functional rhetoric to constitutive rhetoric. 3 authors have been very important in the theorization of rhetoric as constitutive, Donald Bryant, Lloyd Bitzer and Thomas Farrell. The functional approach can be reduced to five propositions:

- Rhetoric is a method of inquiry into communication about the real or contingent.

- Inquiry into the contingent yields opinions of varying utility, but not certain knowledge.

- The proper way of working for rhetoric is in public debate.

- Rhetoric is concerned with deliberation and decision making, it is audience centered it is not universal or imaginary it is historically concrete and specific.

- The deliberative engagement is temporally bound within a context but not universally.

Under the functional approach, these 5 propositions are the limits of rhetorical theory. However, the constitutive treatment of rhetoric goes beyond these limits. Those who theorize rhetoric as constitutive hold that rhetoric does not just convince, but it constitutes the subjectivity of the audience, it is epistemic and ontological. Post-foundationalist theories have a strong affinity with the constitutive notion of rhetoric. Rorty holds that conversation is rhetorical in this sense, Fish holds that something is rhetorical in this sense.

A good example of this way of approaching rhetoric is Deman’s discussion of Pascal and the zero. For Pascal the number occupies a very special position, it is and is not a number. While it does not describe a plurality all other numbers are based on it. This can also be seen in the case of time and of movement. Stasis is necessary to establish movement, the instant is necessary to establish the flow of time. In the case of number zero is the establisher, it is not a number, it is the abscense of number. In this case, Deman claims that by naming the unnameable as zero I transform the zero into a 1 and that this process is catachresis it is rhetorical.

2. Contingency in Politics

In the traditional Marxist theory of history, necessary laws assign meaning to events; knowledge consists of relating the empirical event to the necessary law. This is an example of the eschatological schema that we discussed above. Under this theory a new mode of production can only follow the exhaustion of the previous mode. All societies must pass through the feudal mode then the bourgeois-democratic allowing the contradictions in each to lead organically to the next. However, when Marxism was put into practice throughout Eastern and Western Europe, this pattern did not hold up. In Germany, the development of bourgeois democracy followed an unorthodox pattern, it was difficult to call Bismark a bourgeois, and in Russian, the development followed an even more unorthodox pattern. Russia had no native class of capitalists, their ‘modernization’ took place by means of foreign capital. In Russia there was certainly a large number of workers at this time, but the mode of production was still feudal and attempting to become bourgeois. Thus, the democratic stage, the democratic revolution becomes contingent, there is no native capitalist class to anchor it; historical necessity is suspended. This problem gave rise to three major positions. Lenin and Trotsky’s arguments are metonymical; they are based on a substitution, Lenin would have people strike together but march separately, Trotsky would have the people march together and view the bourgeois revolution only as a bridge to socialist revolution. The three positions are given below.

- Classical Posititon (Right Social Democrats)- the revolution will be bourgeois democracy.

- Lenin (Bolshevik)-The bourgeoisie is incapable of the revolution so workers and peasants will carry it out and enact democratic reforms.

- Trotsky- If the workers and peasants seize state power, the capitalists will attempt a lockout. The only solution is the dialectical transition to socialism achieved through a permanent state of revolution.

This problematic lead to the development of the theory of imperialism which holds that the world economy is not simply a collection of disconnected phenomena it is an imperialist chain, it is linked. If there is a disruption of the world market in one place, that will create a disruption in other places. Thus, seizure of the state is possible without development of production in the national economy. In situations of combined and uneven development, the political exceeds the economic development. So we see that the metonymic situation above fades into metaphor, it is not a substitutive relation but a relation of combination; the relation shifts from a substitution of historical actors to a combination of areas at different levels of productive development. This is as for as things went in Russia, eventually their revolution, which could have succeeded provided that it induced a world revolution, turned back against itself when it renounced this goal.

In Italy, Gramsci looked at this situation and theorized it somewhat differently. For Gramsci, society is a set of unconnected elements made into a whole through hegemony.

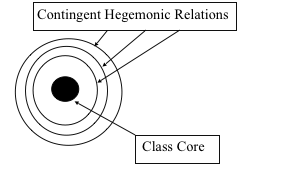

The hegemonic relations are contingent relations. For instance, if the democratic revolution is only associated with the bourgeoisies it will be a certain way, if it is associated with the workers it will be a different way. For him class-character is not determined by necessity, there is a class core but there are also hegemonic and contingent extensions persons who identify with that which is not determined by their class position. The contingency of the hegemonic connections are a major factor in politics. For instance, consider the connection which has been established in recent years between liberalism and democracy. In the 19th century, liberalism and democracy were not connected at all. Liberalism was associated with ‘lasseiz faire’ and democracy was denounced as ‘mob rule.’ This should lead us to question the conceptual as a field of necessity. Gramsci takes us to the field of contingency where we discuss names. The whole is not conceptually determinable, it is contingent, it is hegemonically articulated. For Gramsci, there is hegemony and there is counter hegemony; counter hegemony breaks the connections of floating signifiers. Hegemony is not only associated with the ruling class, hegemonic articulations can come from any strata in the society.

The hegemonic relations are contingent relations. For instance, if the democratic revolution is only associated with the bourgeoisies it will be a certain way, if it is associated with the workers it will be a different way. For him class-character is not determined by necessity, there is a class core but there are also hegemonic and contingent extensions persons who identify with that which is not determined by their class position. The contingency of the hegemonic connections are a major factor in politics. For instance, consider the connection which has been established in recent years between liberalism and democracy. In the 19th century, liberalism and democracy were not connected at all. Liberalism was associated with ‘lasseiz faire’ and democracy was denounced as ‘mob rule.’ This should lead us to question the conceptual as a field of necessity. Gramsci takes us to the field of contingency where we discuss names. The whole is not conceptually determinable, it is contingent, it is hegemonically articulated. For Gramsci, there is hegemony and there is counter hegemony; counter hegemony breaks the connections of floating signifiers. Hegemony is not only associated with the ruling class, hegemonic articulations can come from any strata in the society.

3.Discussion

Affect plays an important role here. It shows itself as differential cathexis, between discourse and affect there is a mutual imbrication. Affect does not exist in a vacuum, it is differential cathexis in a signifying chain. Affect relates to the paradigmatic the associative substutive axis.

To study the performative, we must ask what act of language is being performed in a given situation. The performative has yet to be theorized fully work by Judith Butler and Eve Sedjwick has been pivotal here.

Displacement and Condensation were crucial terms in Freud. Lacan saw that they were correlated with metonymy and metaphor. In displacement one element plays the role of another, as in the case of political opposition which is translated in passionate loyalty to a football team.