Laclau Notes Session 3

by Mark S. Lennon

Review of the History of Rhetoric in Relation to Philosophy

1. The Ancients-Form and Matter

For the Greeks, what is sayable of an object is universal, but we must ask, what is the “it” which receives the predications? For the Greeks all predicables are universals; they make up the form or the rational and knowable part of the entity of the object. The “it,” the irrational and unknowable individuation that remains when you take away all predicables, is called matter. The Greek thought of the universe as a scale. At the bottom was the unnameable primary matter hyle. The first principle of organization was the mineral world where form was imprinted on this primary matter. The mineral world was as matter to the vegetable world, the vegetable to the animal, the animal world to man, and on top the Gods were pure form and stood as matter in relation to nothing.

In this system there was no personal God, there was a formal principle, with the form/matter distinction there cannot be an ultimate source. For Plato the basic action of the Demiurge was bringing ideas and formal principles into being. He includes no notion of an ultimate source; the duality between form and matter is irreducible. He claimed that corruption was the prevalence of matter over form, that living things decline until they are reduced to matter. Aristotle held that perfection was the most developed form. He divided things into potentiality(tree) and actuality(seed) and held that rationality was always threatened by formless matter. This distinction can be seen to mirror the distinction between the master class and slave class in the Greek polis. It had a huge impact on the conceptions of philosophy put forward in the Greek world.

Plato held that philosophy is always formal, conceptual and universal, under no circumstances is it material. If something escaped philosophical knowledge it was to be considered corrupt, as a form of degeneration. For Plato as we have already seen, everything has its degenerate form. He held that rhetorical knowledge can only be a means of manipulating the multitude, “sophistry,” not knowledge, but opinion. For Aristotle the analytic judgment was the highest form of rationality. It proceeded by establishing axioms and showing what followed from them by strict demonstration. However, for Aristotle we cannot use this form of judgment in daily life, we often have to make decisions based on similitude rather than necessity [We can compare this with the Sunday Skepticism of David Hume]. These decisions are based on rhetorical knowledge. This led Aristotle to study rhetoric, not to condemn it as Plato had.

Aristotle divided rhetoric into three genres: the deliberative, the judicial and the epidectic. In the deliberative what is at stake is the determination of what is useful for the community, we can’t have apodictic certainty but we can reason based on probability. In the judicial the value at stake is the determination of what is just, we are also denied total certainty in this case. In the epidectic we are not dealing with a value like the just or the useful, we are dealing with the beautiful. This genre is composed of the funeral oration and other similar commemorative occasions. According to Perelman, the epidictic brings about a dimension which consolidates a course of action, as we can see in Demosthenes orations, or Antony’s speech to the Romans after Caesar’s death, they reinforce the will of the public and they can participate in the political life of a people not only the civic life.

In summary, the Greeks have a distinction between form and matter in which form is privileged. The notion of imperfection or degeneration grants rhetoric its status as subordinated to real knowledge. Plato is totally on the side of form, he has a great distaste for rhetoric. Aristotle’s position is more complex. In his philosophy there is the notion of phronesis or practical reason which is viewed as significant and connected to the use of rhetoric. The Greeks invented the word rhetoric but the Romans were possibly the most rhetorical people ever. This art found a home on the Italian peninsula thanks in part to Greek teachers, but also in part to eager Roman students.

Rome began as a republic. In a republic there must be people who are capable of arguing for courses of action when the state comes to a major decision. Romans did not have the same sense of fantastic abstraction as the Greeks they were a far more pragmatic people. The Platonic posture did have its defenders in Rome, but the art of rhetoric flourished generally. When Rome shifted from republic to Empire a change in the being of rhetoric also took place. Command replaced speechmaking, and arguments. There was no longer as much of a need for orators to persuade the public to act in certain ways, those men were considered enemies of the Caesar now. This new conception of rhetoric can be seen in the work of Quintillian who attempted to codify the ancient rhetorical teachings. After Quintillian, rhetoric would be considered the art of ornamentation. Rhetoric would be seen as the art of speaking well, if you could say things well you could speak the good. One who can do this has an expertise; each profession has its own, but only one speaks of the good of humanity as such he is the rhetor. This is a profoundly ethical notion of rhetoric. This corresponds to the Roman notion of truth. For the Greeks truth was ‘aletheia’ things unveiled their own objective being, showing themselves as they are. For the Hebrews, truth was emmunah, the dependable one. For the Romans truth was veritas, people were lead to ask who speaks the truth.

From its emergence, rhetoric has been composed of 2 aspects, the theory of argumentation and the science of tropes. The first asked what it was to give a good argument without certainty, the second catalogued the figures that orators employed. The further we advance in antiquity the more the second comes to prevail over the first. The prevalence of the second comes with the decline of the republican form of social organization. In the court culture, it becomes more important to speak with grace than it is to present or analyze arguments. When we look at Plato’s scorn of rhetoric in the context of this fact, it seems to correspond to his contempt for democracy, his elitist politics. It is interesting to note that we can find something similar in Aristotle; when he advocates a regime that mixes democratic and oligarchic tendencies this seems to correspond to his more complex orientation toward rhetoric his recognition of rhetoric as important but subordinate to analytic judgment. As we see here rhetoric and politics are bound up tightly, one’s perspective on politics determines one’s perspective on rhetoric, those who favor elitism scorn rhetoric while those who favor bourgeois democracy (i.e. mixed regime with oligarchy) accept rhetoric but subordinate it.

2. The Middle Ages to Modernity

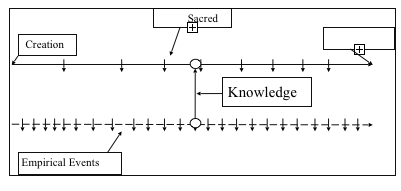

The ancients believed in a principle of rationality without any absolute source. In the middle ages this would be replaced by the Christian doctrine of ‘creation ex nihilo.’ According to this doctrine, God created all that exists from absolute nothingness. It follows from this doctrine that the ultimate source of everything is not rational; the signs of God, as the philosopher said, are inscrutable; through revelation people have access to what will happen but not to the ‘why.’ This gives rise to the eschatological interpretation of history. Below is an illustration of the eschatological idea of history.

The top plane is the sacred or the universal plane and the bottom is the profane or empirical plane. In this type of system, knowledge consists in referring empirical events to the universal plane using language. In this system, reality is multi-layered, persons seeking to create knowledge in this system will need to employ a hermeneutic process to ascertain the correct linkages between planes. The hermeneutic of this knowledge regime is essentially rhetorical. The hermeneutic is centered on the idea of incarnation, in which there occurs a radical displacement that reveals unteachable universal meaning by divine intervention. However, the evidence of such intervention is not provided, in other words, it rests on an appeal to ethos, or an appeal to the authority of the individual who claims to have been touched.

In the Middle ages, education consisted of the trivium: logic, rhetoric and dialectic. Dialectic was the study of argument, while rhetoric was the study of speechmaking. In rhetoric one would give a speech to an audience, in dialectics one would have a discussion with an interlocutor. Thus, we can see that Plato is retained here, probably through the mediation of the Romans. The eschatological interpretation of history seems to duplicate his subordination of the empirical world to the world of forms. However, Plato practiced what we might call ‘sacred ontology’ focusing on objects, while the middle ages were focused on events. This way of viewing history would soon be eclipsed by rationalism; however, the idea that the ultimate source is irrational and that knowledge can come through incarnation or revelation would prove quite stubborn .

The middle ages postulated a fixed correlation between the universal and empirical planes. Today there is a suggestion of contingent correlation if we deal with eschatology at all. Between these two ways of thinking there was the intervention of rationalism. We can think of this as the transition from theism to deism to atheism. The middle ages believed that God constantly intervened in the world, the rationalists believed that God made the world and then let it run its course, and we today people have no need of even that hypothesis. When Spinoza gave us his “Deus sive Natura” when he offered us the idea of nature as the ultimate source, it was in the context of a theory of immanence, not an eschatology. This must have lead many to feel that history was only an unordered series of events which were meaningless and disconnected. In order to restore some coherence to history, in order to reterritorialize after Spinoza’s act of deterritorialization, the SOURCE had to be relocated to the empirical axis. This lead the persons writing at this time to use rationality as the source and attempt to explain the empirical by laws internal to it, it also lead to the development of philosophies of history.

The rationalist moment was a bad time for rhetoric. The reterritorialization via rationality lead to the dominance of analytic reasoning and the marginalization of rhetoric. Rationality was not just rationality, in this context it was the source and as such it had to be universalized and all opposition had to be either discredited or silenced. Descartes is a good example of this, according to his philosophy we had to set aside all which did not admit of absolute certainty, nothing which does not admit of rational proof is to be admitted into philosophy. This type of militant fanatical rationalism is somewhat tempered in Liebnitz. He claimed that the Cartesian program could be realized if we substitute the calculation of probabilities for rhetorical knowledge. Rhetoric was dissolved in this period and absorbed partially by literary studies; at this time in philosophy rationality dominated all argumentation and only the study of the tropes remained. In the 18th century Dumarsais published a rhetorical treatise and in the 19th century Fontanier published the last rhetorical theory to be seen until fairly recently, as a taxonomy of tropes it did not concern itself with epistemic matters at all.

Recently, rationalism has broken down in the same way that eschatology broke down under the rationalist assault. Both retained rhetoric as a supplementary and marginalized field which could only concern itself with ornamentation and tropes. For Aristotle, as for the rationalists, theories had to start with axioms and then by demonstration/deduction proceed from axioms to logical conclusions. The axioms were probable starting points grounded in a consensus of the wise (or self-evident truths), and this process would yield universal truth. Today, axioms do not have to be accepted by all and the idea of self-evidence is less credible, but theorists still derive conclusions; the modern theory produces a fictitious universe, in other words it does not purport to be the physical world, but a way of understanding the physical world, a mediation. The period of eschatology correlates with the period of feudalist hegemony in politics and the period of rationalism with bourgeois hegemony. In the last instance, both of these periods were periods of apologetic philosophy and of exploitative rule. It is not terribly surprising that the first resurgences of rhetoric took place in the 1960’s an era in which the hegemony of capital was radically challenged all over the world. Kuhn and Feyerabend in the philosophy of science are crucial examples of the breakdown of rationalist domination. Kuhn held that scientific paradigms were not expressions of facts, but mediators between us and the world. Thus, the transition between paradigms could not be explained using the rationalist framework. Feyerabend, in an even more radical sally, advocates a break with the idea that science must be regulated by a universal method corresponding to the one universal rationality. In the field of rhetoric, the work of Chaim Perelman, Kenneth Burke and Gerard Genette announce the reascendancy of the study of argumentation within rhetoric, and the return of epistemic significance to rhetoric which had been so long usurped by the rationalist consensus.

2.1 Perelman and Obrets-Tyteca

In their treatise The New Rhetoric, P&O seek to provide a theory of argumentation. A theory of argumentation differs from a theory of logic in that it does not study demonstration. The field of logic has been dominated by the study of formal demonstration, as in mathematics. This treatise can also be read as a contribution to logic, but the subject of this treatise is not formal and demonstrative logic, P&O set out to study informal logic. They begin their study by defining the limits of communication; the limits are, the presence or absence of a common language, the rules of the discussion taking place, and the ability or right to speak insofar as some possess it and some are denied it. They also discuss the distinction between conviction and persuasion. Kant made conviction universal and persuasion particular in his theory, conviction corresponded to fixed truth and persuasion to the will. When one communicates conviction, one addresses the universal audience, not any particular audience; in other words one addresses ‘Reason.’ This is due to the fact that when one addresses any particular audience it is necessary to accommodate their constitutive premises. If we are Kantians, we must consider persuasion as something irrational and hence unphilosophical and the study of persuasion to be pointless and impossible.[But consider also Schopenhauer’s ‘eristic’ dialectice.] Perelman argues that there is an argumentative rationality which philosophy can and should study. This break with Kant is emerging as a consensus which grows stronger against the idolization of rationality as a substitute for God.

Appendix on immanence and the problem of Evil

If God is both perfect in goodness and all mighty why is there evil? This question is a very difficult one for many people to answer. Augustine tried to respond to this question but he failed, when he said “the signs of God are inscrutable” he demonstrated by failure that faith itself may be a lie. Luckily, this embarrassment did not stop later theologians from attempting to answer this question. The answer to this question came in the form of the philosophy of becoming a.k.a the philosophy of history. During the Carolingian Reinnasance Scotus Erigena formulated a philosophy of becoming not unlike Hegel’s. This philosophy held that the present is an illusion and that evil is an illusion, that it is in the service of the greater good. If we adhere to this doctrine, we must maintain that God is not yet perfect, but becoming perfect; we also do not believe in transcendence, God is not outside of creation. ‘Deus sive Nature’; this seemed to some to be pantheism, the belief that everything is God. Hegel Marx and Spinoza have this in common; Spinoza believes in total immanence in Nature, Hegel in the idea, and Marx in history. It seems that all of these theories of immanence have been forced to deny the reality of the present in favor of some future reconciliation, which will rationalize evil fully by achieving perfect determinism. For Christians it is the Last Judgment, for Hegelians the full realization of the Spirit, for Marxists it is the achievement of communism, for each of these approaches are based in the eschatologic that we discussed above; these theories tend to dominate existence with necessities. They seem to deny negativity because if negativity is a constitutive element of existence that is incompatible with full immanence, it makes existence essentially contingent. Contingency describes things that exist but might not have, this is the non-coincidence of existence and essence. This is an essential deficiency; this is a deficient being, its essence does not involve its existence. Accidentality describes things that are empirically given, a characteristic such as nose length is a given but not by necessity. If a theory does not incorporate essential negativity then it dominates existence with necessities which transcend the apparent contingency of existence.

Discussion: i.e. my critical response to the day’s seminar session

What about a non-eschatological theory of immanence, an a-theological theory of immanence? This type of theory seems to be at work in Nietzsche, Bataille, Adorno, Deleuze and Guattari. These are theories of overflow, they are theories of excess, of positive non-identify. These thinkers emphatically reject the essential negativity and the essential deficiency of being, they hold that there are not lacks but overflows. We attempt to impose various conceptual structures on becoming and it exceeds them. If we accept that being is becoming and that everything is immanent to that becoming we do not have a way of perceiving a deficiency in becoming; we must break it down into being in order to comprehend it. If becoming is not determined by any necessary ends, then theories of immanence do not dominate existence with necessity, they in fact liberate existence from necessity. Lack is an imposed necessity, the slave lacks his freedom because the master imposes upon him the necessity of toil using the threat of murder. Those who claim the existence of a constitutive lack in becoming confuse our ways of regulating existence with becoming. If we confuse these two we find that existence lacks its wholeness because of the death of a God that never existed. When we seem to perceive a lack in existence we perceive an overflow of desire beyond existence. If we are to stay a-theological we maintain that there is no ‘beyond existence.’ Similarly when we describe the non-closure of a system as a lack, we can also describe it as an overabundance that overflows all attempts at closure. Or we can ascribe it to the deluded mystical strivings behind the concept of closure as a goal.

Those who claim that excess as a relation presupposes lack reverse the relation. They also claim that assertion presupposes negativity. This is supposed to be true because these relations work together, neither can work without the other. Though it is true that these work together, something can only lack relative to an assertion because meaning is immanent to becoming thus it is not a priori, nothing is a priori because it is all changing; negativity is relative to desire, it is not a constitutive element of desire, but a characteristic of metrics used to channel or control desire. Desire mirrors becoming which is perpetual overflow. Negativity is an epiphenomena of assertion, in some cases it is the form that stifled assertion takes. If we assert negativity based on the fact of the contingency of existence, we must do so with a pejoratives valuation of contingency as inferior to necessity. If we affirm necessity it follows that we affirm being over becoming, because an a-theological ontology of becoming does not hold that anything at all is absolutely necessary. Theological or eschatological theories of becoming hold that there are inscrutable necessities in becoming, and these deny the becoming of becoming for its eventual or actual realization in some kind of reconciliatory God-term. This is true of the Hegelian and Catholic systems. Though Marx does employ the dialectic, he does not assert this reconciliation; what he gives is a call to active intervention to manufacture a particular becoming. This differs radically from the passive idealist theories in which people are called upon to sit back and watch as history realizes itself.

Earlier we discussed the hypothesis that the simultaneous necessity and impossibility of closure can be explained as a constitutive lack. We spoke of the ‘failed’ totality, of the system without closure. What compels us to judge relative to an impossible totality? This situation may be described in terms of excess as well as lack. When we discuss something in terms of excess we assert that it is more than it is; when we discuss something in terms of lack, we assert that it is less than it is. Excess is the organizing term for an active theory while lack is the organizing term of a re-active theory. The fundamental deficiency of being is an aesthetic tenet which has no meaning for anyone who lacks theological nostalgia. There is nothing for it to lack relative to but some sort of transcendental god-term. In this case, life will be defamed as inferior to some kind of beyond, and we will be knee deep in the worst sort of mystificatory metaphysics. One could almost assert that theories of lack are masochistic theories flagellating themselves before the altar of totality.

Instead of seeing history as lacking eschatological meaning, theory must re-conceive history. The theories of the past established their necessity by claiming that without a transcendental plane history was meaningless. However, if we reject these theories we must also reject meaning as they conceive of it. We do not want history to have a meaning if meaning presupposes eschatology. For it is eschato-logic which dominates being with necessities. We should not mourn the lack of an ultimate meaning which was predicated on a lie to begin with. We need to stand up to the eschatologico-teloglogical threat. We can begin with Marx’s remark on Darwin,

When Marx read Origin a year later, he was just as enthusiastic, calling it “the book which contains the basis in natural history for our view.”2 In a letter to the German socialist Ferdinand Lasalle, he wrote:

Darwin’s work is most important and suits my purpose in that it provides a basis in natural science for the historical class struggle… Despite all shortcomings, it is here that, for the first time, “teleology” in natural science is not only dealt a mortal blow but its rational meaning is empirically explained.3