Laclau Seminar Notes Session 2: Floating Signifiers and Heterogeneity

by Mark S. Lennon

- The Moment of Hegemony

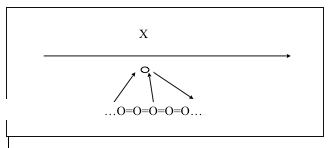

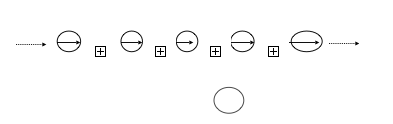

This is a simplified depiction of the moment of hegemony. The X represents those on top of the frontier. The antagonistic frontier can be said to be power, the X is sometimes a government. It can also be the ruling class within a society. The O’s below the frontier are the oppositional desires or the demands of those who are below the line. The oval which is raised above the Os is the empty or hegemonic signifier, the arrow shows its origin from a particular desire or demand. These particular demands are arranged in an equivalential series by the emergence of the hegemonic signifier, the universalization or emptying of the hegemonic signifier is represented by the lines stretching from the oval to the chain of Os.

This is a depiction of a situation in which those who are below the frontier of power have a series of demands which are unmet, and though their demands are different from one another, those who have these differing demands come to see them as equivalent and form a group under the articulation of one particular demand which comes to stand for opposition to X. For instance, if many people have needs which are unmet in present day America, such as the need for affordable housing and health care, the desire to have more efficient garbage pickup in their neighborhood, the desire for a humane foreign policy and so on, they may end up campaigning for these diverse goals through the mediation of a group which articulates a different demand. If these demands remain latent in the population, at any given moment if another group launches a large scale protest those with latent demands may join it even though it does not articulate their particular concern because it articulates unmet demand.

The X is in fact a group of people. In order for them to maintain their position above the frontier, they must restrict the formation of such an equivalential logic. If those who live under power can form a large enough equivalential chain they can overthrow those who are not meeting their demands. There are two means by which the X will seek to keep the equivalential chain from forming, by articulating a logic of difference, or by constructing an alternative logic of equivalence.

- Complications

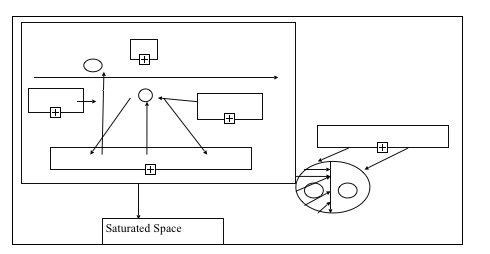

The above diagram is a simplified picture of the hegemonic process. The simplification rests on two assumptions: the assumption that the frontier is stable, and the assumption that any demand opposed to what is above the frontier will be inscribed within the equivalential chain. In what follows we will see how the frontier is displaced, and examine the problematic of inclusion and exclusion in the equivalential chain.

Displacement of the Frontier

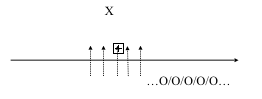

Logic of Difference/Differential Logic/Divide and Rule

This is a depiction of the logic of difference. The ‘/’ stands for non-equivalence or difference, hence the name of the logic, the logic of difference. We can see that the antagonistic frontier has shifted, as we shall see, this is also the case whenever a floating signifier is in play. In this case, those beyond the frontier terminate the possibility of the emergence of the popular empty signifier by eradicating the means of emergence of the chain of equivalences which depend on opposition to what is beyond the frontier for their identity. An example of this type of arrangement is FDR’s New Deal, in which the state tried to mediate the potentially revolutionary demands of an unruly populace by funding social service agencies; each demand is referred to an agency and is kept distinct from all of the others. This is a characteristic of what Marx called Conservative Socialist regimes, which employ a welfare state to mediate certain injustices of capitalism. In this case the people are atomized, they do not come together to deal with their demands, but they go as individuals to deal with bureaus or administrators. What the logic of difference presupposes is that all social demands can be fulfilled in a friendly administrative fashion. Under this type of logic, immigration activists protest immigration issues, peace activists protest war, feminists protest pornography, labor activists protest wages and safety issues, human rights activists protest the actions of foreign regimes; these protests maintain a logic of difference in the masses which keeps them separated from each other and from their collective power. The tactic of divide and conquer employed by many colonial regimes is a means of creating and maintaining a differential logic.

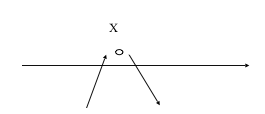

Co-Optation/Floating Signifier

Another means that can be used to thwart the emergence of a logic of equivalence is the creation of a logic of equivalence in which the empty signifier is located beyond the frontier, in this case it is called a floating signifier rather than an empty signifier. The empty signifier emerges in opposition to what is beyond the antagonistic frontier whereas in the case of the floating signifier the frontier is displaced, or the signifier is floated up beyond the frontier. Thus, the opposition to what is beyond the frontier is appropriated by those beyond the frontier, it is mediated by the displaced frontier as in the case of the logic of difference. Laclau stresses the fact that no element is purely empty or purely floating; there is an element of emptiness and/ or floating in every element. The history of populism in American is a good example of the floating signifier in action. Populism in American started in the 19th century with the left, with the struggle of the farmer against the bank and the struggle of the worker against capital. The Populists sought to embody the concerns of the small man or the common man against big business; the populists were concerned with the welfare of this little man against the powerful. They thought that the small man should be the one who dictated values in America. Then, in the 1950’s and 1960’s the right wing began to appropriate populist signifiers more and more. We can see this in the case of the infamous Joseph McCarthy who used a whole arsenal of populist themes in his right wing cause (the average American has been betrayed…). George Wallace also employed classic populist themes while portraying himself as a worker. Nixon’s, as well as Regan’s, rhetoric was permeated by populist themes despite the pro-business right wing orientation of their policies. We can also see this in Italy in 1943-1945. When the King signed an armistice with America, Mussolini who was based in the north of Italy at that time appealed to the Italian populace in terms of the radical republican tradition. At the same time, the communists were broadcasting from Milan claiming that they were the “true Garibaldi and the true Mazzini” because Mussolini received support from the Germans. We must also note that synecdoche metaphor and metonymy are central to floating a signifier. If Benito had succeeded, he would have floated a popular symbol, that of the resistance to foreign occupation, and it would have floated across the frontier making his regime the heirs to popular resistance instead of its opponents.

Inclusion in the Chain

Above is a representation of some Os unlike those in the earlier pictures. These O’s are adjusted to account for the internal difference within the equivalential chain, its heterogeneity. When the Os or demands enter into the equivalential logic, when they come under the empty signifier, they are fissured. These fissures(the lines in the picture) occur when demands that conflict with one another are included in the chain. The equivalential logic is able to reduce the conflicting particularity of the demands, it reduces their heterogeneity, but it is not able to reduce all conflicts. Below the chain is a demand that stands alone. It has been expelled from or denied access to the chain. This type of demand is called the radical outside. Only those demands which are included in the chain are allowed access to the field of representation. The first diagram, the one that depicted the moment of hegemony assumed that the equivalential chain provided full representation without omission. That this type of saturation of space does not occur is evident because if this saturation took place the frontier would never be displaced. An example of this type of heterogeneity can also be found in the American populist movement. When this movement started farmers were in opposition to big money, but the only farmers whose demands found representation were the white farmers because their demands excluded Blacks, Latinos and Asians. Then, when the populists supported Bryant in the election against McKinley they had trouble establishing a logic of equivalence to oppose McKinley and his pro-corporate progressive candidacy. This dominance of right wing discourse continued in America until FDR was elected.

- Marxism and The Radical Outside

Two solutions to this problem of heterogeneity have been put forward. The first is the traditional Marxist solution. This solution, though it does take account of heterogeneity must be rejected. In the traditional Marxist solution, the representation space is totally saturated by knowledge. In order to make the movement from A into B I only need to know the contradictions in A. In his theorization, displacement or quantitative change is ultimately predictable from internal contradictions. For the traditional Marxist the coherence of historical development is production; at each stage of history, we find the productive forces and the corresponding social system. The unity of forces and relations of production correspond to a category of measure that is the higher unity of the quantitative and qualitative. In this system, there is no place for a radical outside. Let us look at Marxism in historical context, and we will see the implications of this omission.

In early 19th Century Europe, culture was arranged in such a way that the recognized social actors all played a certain role in the social field. Within the confines of this group, social space seemed to be completely saturated; all were represented. However, the poor had no place in this social field; this was a gentleman’s club to which they along with other groups were denied admittance. In 1830 in Germany, this problem begins to become more urgent. Poverty begins to become a very serious and insistent concern, the new form of organization seems to be incapable of responding to this issue. Hegel even suggested shipping the poor to foreign colonies. These outsiders were referred to at this time as the rabble insofar as they were included in political analyses, but in time this rabble was displaced by the proletarian poor, who had no place in any stable social description. This destabilizing force eluded many who sought to assign meaning to it.

In his philosophy and economics, Marx would assign these proletarians a central role. Some proletarians would be considered by Marx to be a main historical actor. For Marx production is the coherence of historical development. He predicted that Capitalist production would lead to a proletarianization of the population, which would precede in turn the showdown between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. The class identity of the proletariat would correspond to their role in production. However, not all of the group which had been called proletarians participated in production. ‘Prole’ had originally meant those who contribute to the state only by increasing the population. Those proletarians who were not part of the process of production were dismissed by Marx as a valueless class without a class identity and without history, as likely to join their comrades or join their oppressors as informers. He called them the lumpenproletariat. Marx’s attempt to fix this boundary in relation to productive labor was very problematic. He had used the same distinction to differentiate the financial aristocracy from the proletariat.

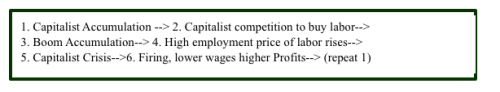

Marx ignored this class within a class at his own peril. Let us consider the emergence of the proletariat(s) from the point of view of the concept of the “industrial reserve army.” This army is created by the cycle of capitalist development. The cycle proceeds as follows.

We can infer that during this cycle there is an accumulation of a marginal mass of those who are unemployed for economic reasons, particularly in steps five and six. By the logic of the capitalist system of accumulation, it makes more sense for the owners to allow a standing pool of desperate workers to develop. If there is more unemployment, employers can get more concessions out of their workers. As this tactic is employed, we can see the lumpenproletariazation of a large segment of the population, even those who are employed find the conditions of their employment to be contaminated with the condition of the lumpenproletariat. In the present day, we hear much talk of the flexibility of the labor market, which means that workers are constantly being taken out of the productive process by layoffs and so on. It seems that the lumpenproletariatization of the masses did not occur to Marx, he may have thought that that would trigger the revolution.

What can we do now, once we have noticed this gap? How can we provide a historical analysis which does justice to social heterogeneity, that does justice to the lumpenproletariat? Must we dispense with the concept of production as the coherence of historical development? Marx himself suggests a path for us. He maintained that when we speak something more is coming out of our mouths than what we think we are saying. In other words, he maintained that history and consciousness are multi-layered. As Stalin would put it, one can be “subjectively innocent yet objectively guilty.” In order to confront this gap we must examine the different ways in which multi-layeredness has been constructed.

- Multilayeredness

We should begin by asking: does outside-ness operate only on the margins of the system? In order to answer this we must examine the concepts of antagonism and contradiction. In Marx, contradiction is the most ‘inside’ relation. The relation which is central to the capitalist system is the relation between worker and capitalist. A dialectical explanation of this relationship would tell us that we can find all that we need to get to the second term in the first term. In other words the B-ness of B is reduced to its not-A-ness. The first step in such an explanation would be a reduction of the terms to logical categories. Thus, the capitalist is a buyer of labor power and a worker is a seller of labor power.

According to Marx, the contradiction here is that the capitalist steals the surplus value from the worker. He gets more from the laborers labor than the laborer does. However, this is only a description of the capitalist means of organizing production. The antagonism between capitalist and worker only begins when the worker resists this theft. In order for the recognition which leads to this resistance to take place, the worker must be placed in a social context which is not internal to this relation of production. The worker must be exposed to an outside of production that is inscribed in the inside; he or she must be exposed to a social context external to production. If we follow Marx, the forces of production at any stage of historical development are only compatible to one set of relations of production. If the worker is exposed to something outside of the relations of production, something which conditions his resistance to capitalist domination, then, we must ask whether history is a discontinuity without the coherence which the concept of production had provided.

- The Nature of the Antagonistic Relation

In order to continue with our discussion we must touch on a debate which raged in the 1950’s in Italy between the Della Volpeians and the Hegelians over the nature of the antagonistic relation. Kant had said that by opposition we can mean either real opposition or logical contradiction. Real opposition is the opposition of A and B such as the case of two cars crashing into one another, where the second car is quite independent of its relation to the first. In logical contradiction, the opposition is between A and not-A where each is exhausted in being the opposite of the other. Kant said that real opposition is between things and belongs to the real order while logical contradiction belongs only to the conceptual realm. La Volpe claimed that it is absurd to think that we have contradictions in reality, that for Marxists to espouse this principle is a betrayal of materialism; a substitution of logical contradictions for social antagonisms. This does not mean that social antagonisms are real oppositions either.

For La Volpe, both contradictions and oppositions are objective relations, one pertains to conceptual objects, one to real objects. Social Antagonisms on the other hand show the limits of objectivity. Consider the case of a group of peasants who are going to be expelled from their lands by a group of landowners. If the market price of wheat rises, they will be expelled, they decide that they must act. This decision to act is not an objective decision. To the peasant, and those who choose to aid them, the landowner represents a radical negation of their identity. The positions of the landlords and the peasants are not objective positions but places of irretrievable negation. Thus, there arises an ontological difference between the peasant and the landowner. In order for this situation to be reduced to objectivity the parties to the dispute would have to be syntagmatically located, but they are not. They each read the situation in a different way, there is no convergence in a unified whole. In order to reduce this conflict to an objective relation one would need the perspective of a rational universal history which transcended the moment of conflict. Some external observer could attempt to place this conflict within a history, but this history could only claim to represent the objectivity of the conflict, not that of the actors.