Plato and Ideology

by Mark S. Lennon

The most significant lesson that I draw from The Republic is that so long as there is luxury–i.e. class rule–there will be deception and tyranny. The ‘city of pigs’ that Plato rejects is the crucial point in the story for me. I read Plato’s utopian writing as more of an exercise in following ideas to their conclusions than as manual for statesmen. What Plato does in this work is he attempts to rationalize privilege and he fails at it. The book demonstrates the fact that privilege cannot be justified without using mass deception combined with censorship and the state sanctioned indoctrination of children. The friends assembled to discuss justice do not reject the ‘city of pigs’ because it cannot be the just city, but because they (being from the privileged class in Greek society) were accustomed to a standard of living that involved luxury goods. If they are privileged and they are the only ones in their society who have access to luxury goods, then to say that the city must have luxury goods is as much as to say that the city must have privilege.

If we read The Republic as a map of the implications of privilege, we must abandon the notion that the chief value of this work lies in what we have been told that Plato intended to advocate. We have been taught to read the work as a utopia avant le lettre; in fact, it is an investigation of justice. The book begins with a dialogue on the topic of the value of justice and the just man. That dialogue leads to an impasse, in which Socrates cannot demonstrate the value of justice in-itself on the established argumentative terrain. He has not succeeded in conclusively refuting Thrasymachus’ logic in which justice is the will of the stronger, the will of the ruler. Thus, he claims that he can make his point by way of an analogy with the just city. The problem is that justice in the ideal city is the will of the Guardians insofar as they define the direction of the society; the ‘noble lie’ which the guardians are allowed to tell in the interest of the state seems to support Thrasymachus’ point of view more than Socrates.’ All Socrates finds is the best possible set of the ‘strongest’ in his guardian class–by clothing them in philosophy he sacrifices the good to might and ends in irrationalism.

In this work, Plato condemned poets. He claims that poets move people by illogical means, that they deform the minds of the young. However, he did allow them a place in society provided they met one of two conditions: either the poet should make songs in praise of great heroes of the past, or the poet should be prepared to make a defense of poetry. Elsewhere, according to traditional readings, Plato accuses the poet of making copies of copies, he claims that their art imitates nature which is itself a mere imitation of the ideas. Thus, the poet does not make contact with true being but is mired forever in the world of appearances.

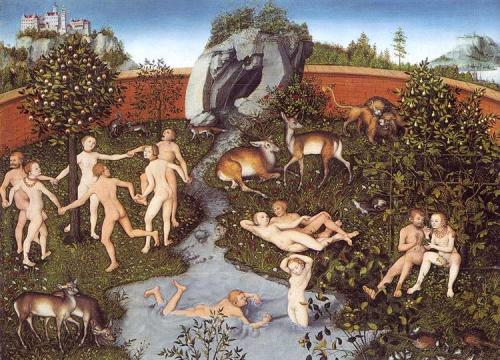

This use of the poet in The Republic is coupled with an educational censorship agenda relating to depiction of the actions of the gods. Socrates claims that the gods should be presented as rational and good in order to teach children how to be rational and good; however, the stories of the poets typically showed the Gods to be all-too-human in character. This is also the case in the Homeric depictions of the legendary heroes, such as the defiant Achilles and the unscrupulously clever Odysseus. Should we obey the injunction to censor these unflattering portrayals, there is a danger that these stories will seem too remote from human life and lose the interest which people attribute to them. But, why is it that these depictions (of Zeus as rapist and Achilles as unpatriotic and self-centered) are so interesting to the people who consume these poetic fables? Could it be that they contain a germ of truth insofar as they dramatize the injustice and brutality of class society?

Plato also would have rulers make use of another educational aid, the myth that human beings correspond to different types of metal, gold, silver and bronze, which form a natural hierarchy. Instead of recognizing such rationalized gods as inhuman, and such myths as outlandish, people would be taught to view the gods as natural superiors, that which must rule them because they are incapable of becoming it. As bronze cannot become gold, so even gold cannot become gods. In The Republic, the distinction between the absolutely rational gods and the all-too-human people would mirror the distinction between the absolutely rational guardians and the all-too-human people at the bottom level of the hierarchy.

We should think of the connection that is established between the ‘luxurious city’ and warfare. The ‘luxurious city’ requires warfare for its continued existence. Thus, the poets may eulogize the great heroes, may write panegyrics about them but they may not write biographies. Perhaps now we can see a deeper logic at work in the suppression of the poet. If the poet portrays the gods in ways that are inconsistent with state cultural regulation, he subverts the reinforced hierarchy which places the Gods as inhuman above the human, he can even call the ‘noble lie’ into question. If the poet portrays life as it is lived, then he will be forced to portray an imperfect copy of the true reality–i.e. he will be forced to depart from the ideological official self-image of society–he will present a reality in which privilege leads to injustice, a reality in which gods rape mortals, and commit other injustices with impunity. The hierarchy of the poets is one of arbitrariness and of injustice, the gods are not good nor are they rational, they are human.

All of these seem to serve a slightly rearticulated Sparta in which one group toils and another group makes all the decisions. Though the Guardians are dressed in the robes of philosophy they remain villains underneath…

II

A second significant lesson that we can learn from this work is that the philosophical tradition is radically anti-democratic. This is not to say that philosophy as such is anti-democratic, but what people call the ‘grand tradition’ of philosophy has roots in profoundly anti-democratic sentiments and we must acknowledge this historical origin. Here we take the term democracy in its most profound sense as the power of the people, the masses, the proletariat.

When we speak of philosophy and the tradition as opposed notions, or as things that can be opposed to one another this is not to say that there is a great concept of philosophy that the tradition itself even fails to exhaust. The reason that this state of affairs exists is simple, it is the result of the contingency of that tradition, those people could have written something different than what they did in fact write, or they may never have written at all, also there is a great chance that many works have been written and destroyed in time, and there is also a chance that the works we have could have been destroyed and those other works retained if other events in history had happened differently. Also, each work in the tradition manifested it in new ways, ways consistent with changing material conditions and social rhythms, each articulation of the traditional thoughts subverted the tradition as it re-inforced it.

What are the basic outlines of this grand tradition? We can locate the emergence of this strain of philosophy across a few hundred years of Greek history. First, we have the so called pre-Socratics, people concerned with finding natural explanations for what had once been explained by myth. These people did not as yet refer to themselves as philosophers, they were engaged in aletheia or discovery, or uncovering. Next, we have the emergence of the sophists as the development of commerce in the Greek economies and societies called the myths and the traditional society they defended increasingly into question. In competition with the sophists, who believed that there were no standards that were not immanent to a particular situation, we have the Socratic school which would find absolute truths and foundations that must govern civic life. The grand tradition derives from the thought of this third group, it represents the quest for rational absolutes, the attempt to provide a return to the security of myth using other means.

This is a losing proposition, it is an attempt which even the most cursory exposure to history will prove absurd in its very conception. Myth provides people with the stability of blind acceptance, something which rational inquiry cannot replicate; reason cannot restore us to myth, it is something quite different in its methods and procedures as well as the types of conclusions it propels us towards. The action of logic, pure logic or pure reason as applied to a set of accepted propositions is a deterritorializing action; it tends to pull them out of the particular context in which they had some claim to validity and place them in a different context that is governed by rules and principles alien to their construction. Logic is not a force that leads to certainty, it is the enemy of any particular certainty as it provides more mechanisms by which said certainty can be disassembled than mechanisms of proof.

This deterritorializing action of logic tends to bring to the foreground the contingency and partiality of any set of so-called truths. All truths come to us in the form of a the ‘if-then’ where the if is a given, is a gift which is never justifiable by anything other than the force of its assertion which can receive no rational justification, but lies in another realm entirely. To drive this point further, if we rigorously apply logic to any set of given propositions we arrive at a number of contradictions and inconsistencies which cannot be resolved within the terms of the system that we are attempting to maintain. Logic is impotent to resolve these because they are of another order, they are of the historical order, thus we can either move from an analytic logic to a dialectical one or we may say, as the scholastics once said, wherever we see a contradiction we introduce a distinction, and this leads to my next point.

If we apply critical thought to logic, we see that any particular application of logic considered as a formal system is totally dependent on the semantics of the terms that we use to fill the variables in the formulae. This being said, these semantics admit of near total variation by means of distinctions and subtle redefinitions of terms. If this is the case, logic can be used to prove the validity of anything that one chooses to prove the validity of. However in this case we have nothing that resembles proof, what we have is the drawing of conclusions whose truth value is indeterminate from propositions that we accept as given. This acceptance as given brings us back to the groundless choice against the city of pigs:

Yes, Socrates, he said, and if you were providing for a city of pigs, how else would you feed the beasts?

But what would you have, Glaucon? I replied.

Why, he said, you should give them the ordinary conveniences of life. People who are to be comfortable are accustomed to lie on sofas, and dine off tables, and they should have sauces and sweets in the modern style.

Yes, I said, now I understand: the question which you would have me consider is, not only how a State, but how a luxurious State is created; and possibly there is no harm in this, for in such a State we shall be more likely to see how justice and injustice originate. In my opinion the true and healthy constitution of the State is the one which I have described. But if you wish also to see a State at fever heat, I have no objection. For I suspect that many will not be satisfied with the simpler way of way They will be for adding sofas, and tables, and other furniture; also dainties, and perfumes, and incense, and courtesans, and cakes, all these not of one sort only, but in every variety; we must go beyond the necessaries of which I was at first speaking, such as houses, and clothes, and shoes: the arts of the painter and the embroiderer will have to be set in motion, and gold and ivory and all sorts of materials must be procured.

Then we must enlarge our borders; for the original healthy State is no longer sufficient. Now will the city have to fill and swell with a multitude of callings which are not required by any natural want; such as the whole tribe of hunters and actors, of whom one large class have to do with forms and colours; another will be the votaries of music –poets and their attendant train of rhapsodists, players, dancers, contractors; also makers of divers kinds of articles, including women’s dresses. And we shall want more servants. Will not tutors be also in request, and nurses wet and dry, tirewomen and barbers, as well as confectioners and cooks; and swineherds, too, who were not needed and therefore had no place in the former edition of our State, but are needed now? They must not be forgotten: and there will be animals of many other kinds, if people eat them.