Consensus and Violence

by Mark S. Lennon

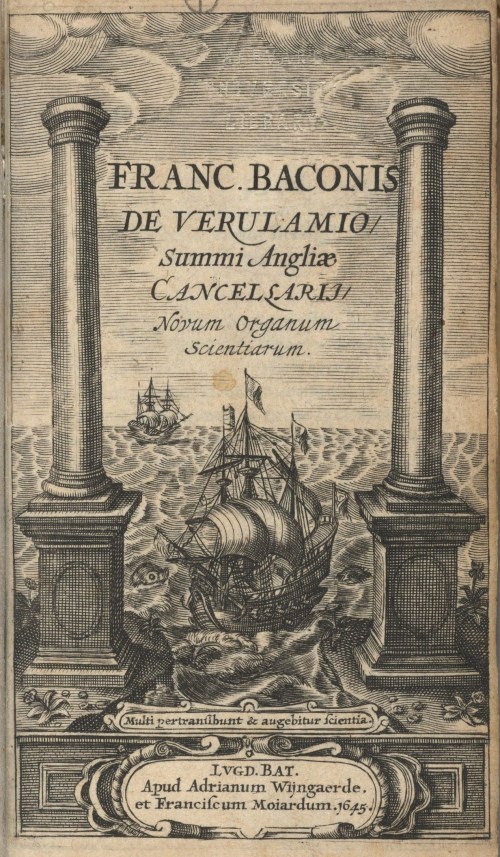

As Lord Bacon said, scientia potentia est: knowledge is power. Bacon warns the inquirer, the natural philosopher against the ‘four idols’– various forms of social prejudice– as obstacles to inquiry, and claims elsewhere that his inductive logic is superior to Aristotelian logic because it can be used to create new knowledge that makes life better, not merely to codify established truths. This seems like a great idea, science alleviating human misery; however, for Bacon, science can only investigate nature, it cannot inquire into matters of church and state.

The existence and efficacy of the sciences and the scientific orientation is proof of the truth of the fundamentals of materialism. Science demonstrates the substance and primacy of matter. Science and society have long tried to distance themselves from this orientation implicit in scientific practice. What if people started to use a scientific approach to their everyday lives? That is a dangerous thought indeed, one which has troubled rulers for many centuries. They face the following dilemma:

- They need to make use of science to remain in power

- They need to repress scientific consciousness in the masses to remain in power

The contradiction we see here coming to birth in Bacon is the contradiction that drives much discourse on the sciences: on the one hand, we have the general principle of scientific materialism–there is a real truth about the external world which can be revealed through sustained material engagement with reality, understanding it allows people to improve their lives–but, on the other hand, we have various forms of idealism which claim that there is no such truth about the organization of society, there can be no such truth about human history these are composed of other stuff.

Idealist thinkers fetishize the ‘scientific method,’ but they ignore the scientific orientation. Typically apostles of method will select a particular science and use some case studies from its history to demonstrate what appear to be general truths about science. Where its physics one is a positivist, where its biology one is a pragmatist. However, some of us grow weary of the merry-go-round of particulars held up as universal, and insist that there is a scientific approach to phenomena that all scientific endeavors have in common. This orientation seems to be little more than a vague adherence to materialism–the discovery truth by making contact with an objectively existing external reality.

Consensus can emerge through 2 mechanisms: inquiry–the ongoing expansion of understanding through exchange and argument, which comes to include to some degree the concerns and insights of all involved, or repression–the exclusion of those who disagree from discussion. Though many are inclined to view only the former as consensus in the strict sense, much that goes under the name of consensus in the real world relies substantially on the latter. In the case of philosophy, consensus is reached on certain matters before we even begin; for other matters, there is room for discussion.

In academic philosophy, we have 2 levels of determination: the philosophical, and the social. The purely philosophical determinations come from the history of human thought. The social level comes from the institution of the university in its sundry connections with the other institutions that support it, and rely on it for support. The apologetic trick is to bury the latter under the former.

A consensus or a paradigm is the result of a coincidence between these two levels. These paradigms typically move through 2 phases: a hyperbolic phase of excitement social cohesion, and enthusiastic overextension, and an ironic phase in which the terms are gradually adapted to accommodate contrary insights until they become meaningless. We can see this in the movement between empirio-positivism and pragmatism. The logical positivist consensus was built on purges of the academy during the McCarthy era which corresponded to the high dogmatism of this model in American philosophy of science and language. This comes to a sort of limit point of irony in Rorty’s willful ‘bourgeois liberal’ nihilism.

To summarize, a consensus in philosophy is a social as much as a philosophical thing. Philosophy begins from certain premises and assumptions which are assumed, and form the basis of inquiry. These are not produced through inquiry, but are produced by social mechanisms external to the purely philosophical. These include selection procedures implemented by the university such as loyalty oaths ‘apoliticism’ and so on. Within these constraints, consensuses emerge as schools or paradigms.