Ethics Practice Becoming

by Mark S. Lennon

Aristotle said that Ethics is not like other forms of knowing. It cannot tell us what is ethical, for this decision must be made on a case by case basis by the individual, but it can look into the means by which one can become ethical. He gives us a very impressive explanation of how one comes to be virtuous; it is through doing virtuous things that one acquires a virtue, so, if I want to be brave, I should do brave deeds then I shall become a brave person. Aristotle calls this type of knowing practical science, this is not the same as theoretical science because it cannot specify details at the same granularity.

It is interesting to consider the relation of means and ends in this schema of virtue acquisition; it seems that the Platonic idea of Virtue as its own end is here faced with the idea of Virtue as its own means. In both of these schemas it can be said that virtue is not a means to any other end, but these two different ways of disagreeing with that idea have very different implications. Ethics only studies the means of virtue, how one becomes virtuous, it does not tell us what is virtuous in detail. For Aristotle ethics is not a metaphysical thing, it is inseparable from politics; for Plato, Ethics is metaphysical and is related to the idea rather than the act.

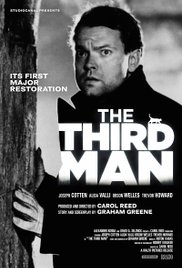

According to Giorgio Agamben, this makes sense because politics is the “realm of means without ends” and also because mythology is the “realm of ends without means.” The realm of the integration of ends and means is everyday life, concrete existence. In politics, every means is a means to set in motion another means, whose ultimate end is always the next means; mythology is making what is into an end without doing anything but declaring it an end. The realm of pure means is the realm of pure becoming, whereas pure mythology is pure being; in our daily lives we sense both change and stasis. Our sensation of change is our relation to the different whereas our sensation of stasis is our relation to the repeated. Of course these things are not really distinct, they are constantly imploding into one another transgressing the boundary. The reason for this is that the idea ultimately derives from the concrete and is explainable in material terms. Thus, if one attempts to speak of the present as finished product, if one speaks mythologically, if one attempts to eternalize the present, this is merely a way of announcing what the future should be. In other words, it is ultimately within the political realm, it is a means to set a means in motion. This has something of the form of the 3rd man argument about it, the political must always witness the mythological, and the political in constant flux perpetually witnesses itself and the mythological with new organs.